Required reading: https://engineering.cloudflight.io/defining-boundaries

A big part of what makes up complexity are side effects. The challenge with them is the (semi) non-deterministic behavior of their execution. A network call can give me the data I want on success, or error out with any of the multiple error codes it can have. Mutations can completely destroy data integrity. This time we will talk about handling mutations.

The Problem Statement

Imagine the following code:

const data = {

foo: 'hello',

world: 'bar'

};

function doSomething(dataToRead) {

const fooValueBeforeCall = dataToRead.foo;

await apiCall();

const fooValueAfterCall = dataToRead.foo;

}

function modifyData(dataToModify) {

dataToModify.foo = 'some new value';

}

doSomething(data);

modifyData(data);

What we see here is reading the property foo does not always give us the same result. This is especially painful for programs with concurrent execution, since the business logic might require certain conditions to be fulfilled.

The modification of the data structure happens somewhere else in the code base. In the example, it is right below our call to doSomething but in reality, it can be somewhere else we do not know. Of course, the code above violates the boundaries.

Inspirations

How can we prevent mutations from becoming the source of bugs, then? We can take a look at how different programming languages handle them.

Haskell

In Haskell, mutations are not allowed at all. Every modification we want to make must be done by returning a new data structure with the changes applied. Mutations can't be the source of bugs if we don't have any, now, do we? Of course, like everything else in real life, this approach also has some downsides. You see, the majority of computers out there are based on the Turing machine, which in itself is based on mutating data. The (low-level) abstractions we use on top of it today also do not deviate from that idea. That is a limitation for Haskell since the low-level details need to be implemented in a way with side effects. Otherwise, the performance suffers because of the discrepancy between what the machine is good for and what Haskell wants to do. Not all of those low-level details can be completely abstracted away, though, thus making Haskell not suited for performance-critical work on the level of C and C++.

Rust

Rust on the other hand competes on that level, so it gave up on the idea of being mutation free. The language found a sweet spot between the two worlds: Mutability as a keyword and the ownership model. Remember what was written in the boundaries article? We want to express as much as possible with the type system and fall back on other solutions if there is no other way. Rust encodes mutability within the type system with the mut keyword. Most code does neither need nor do modify data, so immutability is the default in Rust. In case we do need mutations, we can use the mut keyword. What would be harder to understand would be the ownership model of Rust. I am not going to explain every detail of the ownership model here. The official docs exist for that. Instead, I will take the bits of interest for us, namely references and borrowing. The constraints from Rust are the following: We can have as many readers of that data as we want, but no writers. Or we can have one writer to that data, but no readers. Doesn't this pattern seem familiar? Yes, it is a read-write-lock, but enforced at compile time, made possible by the type system.

Defining the Architecture

We can use those two systems as inspiration for how we should manage mutations. Following the Haskell approach fully won't work, since we do have global state in the Frontend, which is the store. Rust has great ideas, but we cannot commit to it either because Typescript has no way to express the ownership model with its type system. Because of those reasons, we need to rely on conventions instead of the type system for what we are set to do.

The Single Source Of Truth

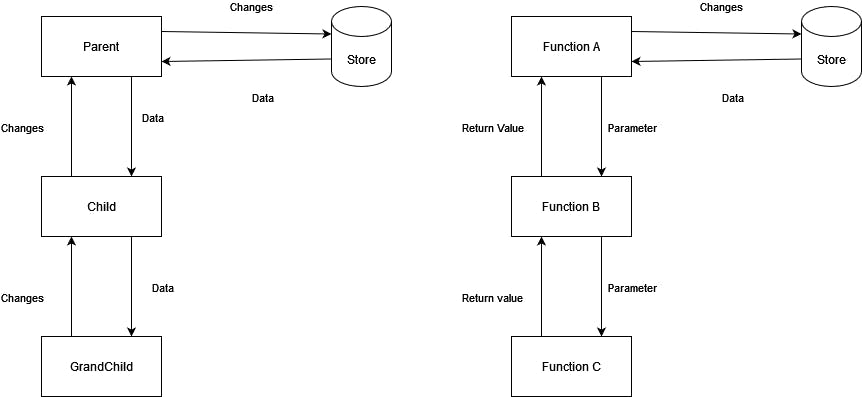

Let's introduce the concept of the owner. Our idea of the owner is a simple one: Where is the single source of truth? Let's say we have a function that accepts some data. Where is the single source of truth of that data? Yes, the caller, because the caller passed in the data to the function. The caller might have gotten the data from its own caller, in which case the single source of truth also shifts up to that caller. Alternatively, the caller might have gotten the data from a store, then the store becomes the single source of truth. See where I am going with this? I am constantly asking where the data comes from and ultimately, we will land at one place, which holds the absolute say about the data and everyone depends on it.

Can we have Typescript express the read-write-lock pattern like in Rust? No. Typescript does not have a way to do that. What we can do, is assume there are N readers, always. In Rust's case, nobody can write to the data. But that is not realistic for us, since mutations are needed to update the state in the store and display user changes in the UI. If we cannot eliminate it, then we can constrain the usage of mutations. Where should we be allowed to mutate? Not anywhere where the data is read, since that will make the reader into a writer, and we must not mix them. We have no way to ensure no readers being existing after all. So there is only one answer to this question: Wherever the single source of truth is. Since everything reads the data from the owner, aka the single source of truth, or a derivation of it, we can also assume that it can handle changes to the data it owns correctly.

A reader needs to communicate with the owner that some changes should be made to the data. There are two ways to make that happen: Tell the owner what to modify or give the owner an already modified copy to replace the data with. The former requires the owner to understand what the reader wants from it. This concept is an interface sitting between the data and the outside world, guarding what is allowed to be changed. The latter exposes the structure of the data fully, which might be more than enough when your requirements are not very complex.

One thing to keep in mind here is every component executes this concept for its own source of truth, which is its caller or parent or whatever it is called. Why can't we just write directly to the actual single source of truth? Because the callee does not and should not know where its caller got the data from. Ultimately, the one piece of code reading the data out of the store or the database is also the one writing the data back to it.

Replace Instead of Mutate

We are not done, though. The aforementioned architecture only makes reasoning easier by grouping relevant behavior together. Assume the following code:

let data = {

foo: 'hello',

world: 'bar'

};

export function modifyFoo(newFoo) {

data.foo = newFoo;

}

export function readData() {

return data;

}

This implementation of the store looks fine, does it not? Accessors for writing and reading are both within the same file, and the data itself is not exposed. But it can lead to the same bug from our first code example. Haskell has half of the answer for us already: Do not modify existing data, but create new ones with the changes applied. In other words, we need to create a new data structure and replace the old one with it.

let data = {

foo: 'hello',

world: 'bar'

};

export function modifyFoo(newFoo) {

const updatedData = {

...data,

foo: newFoo,

};

data = updatedData;

}

export function readData() {

return data;

}

Now, with the new implementation, the bug from our first code example is also solved.

One question worth asking would be calling readData multiple times can lead to returning different data. Did we really fix the bug? The answer is yes. Reading from the store itself is considered a side effect, since the store is just a global variable with some abstractions around it. The bug we fixed is reading data from the input parameter always returning the same data, done by not mutating existing data anywhere.