Defining Boundaries

Managing complexity is a discipline on its own, and many books have been written about it. Regardless of which ones you mastered, compartmentalization of impact will always be on the top list. Let's say we have a very big code base, and we want to do some changes there. We did the change and now something somewhere else is broken. Without proper compartmentalization, any adaptions in code can break any other part of the codebase. Imagine the horror: We would need to test every possible combination our software is used to make sure nothing is broken. Not only that, the confidence to refactor is lost and nobody dares to touch existing code anymore. For this very reason, we need to break up code into smaller pieces and set boundaries between them.

With that being said, how do we do it? Initially, I wanted to reason that code should not pass behavior around, but communicate in data, like only with input and output data. This approach has served me well wherever I applied it and seemed like the truth for me. When I tried to reason why this is the best practice, some other programming patterns made me question my view: What about higher-order functions? It does inject behavior. I also use them a lot. The same question can be asked for plain JavaScript. Do I have confidence that the input parameters I get are of the correct type? No, not really. I don't know the type of data. There was a blind spot in my knowledge I did not realize before.

Starting from Zero

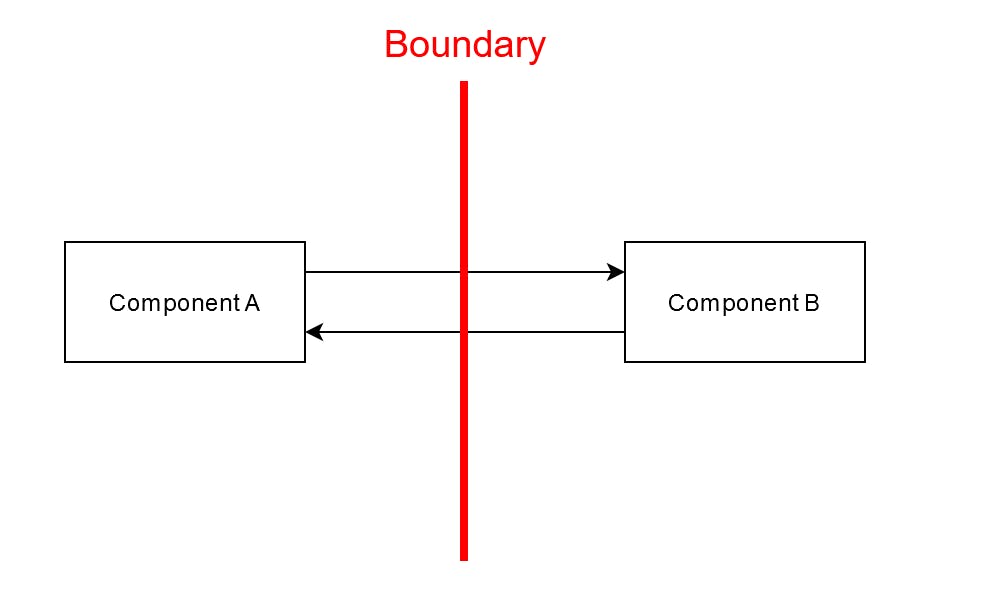

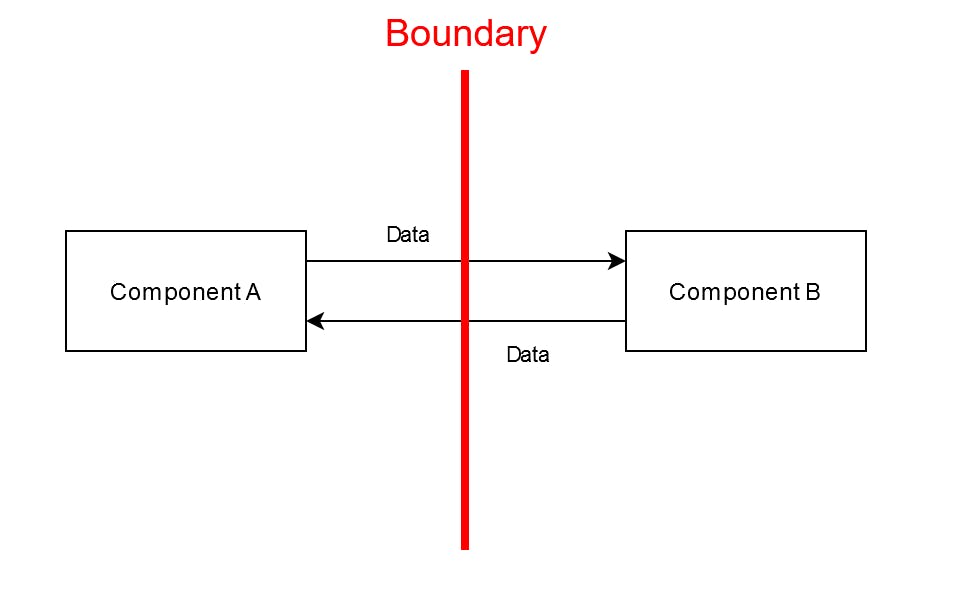

So let's start from the very beginning instead. We have pieces of code, some get called and some call others. What we want to achieve is when we do a change in one of them, we want the area of effect to be as small as possible. We can do that by establishing clear boundaries between the code. The first question we need to ask is, what are boundaries? Boundaries are ways to communicate characteristics. I accept data with the following characteristics. I have the following characteristics when executed and so on. It is the language of defining contracts. The second question is, what ways exist to define those contracts? From my experience, there are many of them, including but not limited to the type system, common conventions and documentation. We will discuss them a little later. The third question is what characteristics do these different solutions have? For what interests us, we can roughly categorize them with the following characteristics:

When the contract takes effect

How the contract takes effect

The effort to maintain the contract

The earlier the contract takes effect the better since a shorter feedback loop improves the productivity of the programmer. The more strict the contract takes effect, the fewer violations there are in the code base. Aborting the build is better than warnings, which is better than ignoring the violations. Of course, there is also the human effort in maintaining those contracts. It is also something that differs from solution to solution.

The Type System

With that nailed down, we can take a look at the solutions, starting with the type system. Imagine the following function in Typescript:

function sort<T>(data: T[], compareFn: (a: T, b: T) => number): T[]; |

There are certain constraints communicated here. The first parameter must be an array of some type. The return type is the same as the parameter data. The second parameter must be a function. Can the caller pass in a boolean as the first parameter? Can the caller pass in a compareFn which returns a string instead of a number? No, not really, because Typescript will fail to transpile your code otherwise. All of this is possible because the type system can handle data models well

.

Type systems are nonetheless not all-powerful. There are constraints we cannot express with them, not even with the best one we have right now. Say, how can we assure compareFn always returns the same output given the input? It can also make a network call in there. Who said that the sort function actually sorts the array? Maybe it just prints “Hello world” into the console and returns an empty array regardless of the input. Nothing prevents those things from happening. Data modeling is a well-covered topic. The challenge for better type systems lye in modeling behavior.

Conventions

For requirements outside the reach of the type system, we need something else to fill that gap. This is where conventions and documentation come into play. We expect a function to do what its name tells us. We expect all the parameters of a function to be used. Likewise, we expect the documentation is true to the behavior it describes. These are social contracts. Contracts between humans and not code. We expect the other programmer to hold onto some convention we all hopefully agree upon. All that is because we have nothing better at the moment. Since there is no strict enforcement of them, it can happen where these contracts are not held. Functions might not do what their name tells us. Documentation can be out of sync and so on.

Looking at the bigger picture, we want to be able to define our contracts in a (contract) language with the fastest feedback loop, is very strict and has the least maintenance effort. Falling back to other solutions should only happen if that language is not expressive enough for our needs. That means we want to define whatever is possible with our type system first and rely on conventions and documentation as a fallback.

Summing Up

The core of any type system is data modeling. Therefore, data models are the primary means of communication between code. Functions receive data as input and return data as output. This puts us back to my initial thought about this topic I mentioned at the beginning. Plain JavaScript does not even have a proper type system. Thus, sending data around itself does not instill any confidence. Now, what about higher-order functions? What if we want to send behavior around? Type systems from languages like Haskell can express some properties of behavior, such as if they have any side effect or what kind of side effect it has. In those programming languages, sending behavior around won't be that much of a big deal, or might even be encouraged. If the type system cannot do that, then we, as programmers, need to fall back to other contract solutions like common conventions and documentation. It does not always work but is good enough to get our job done.